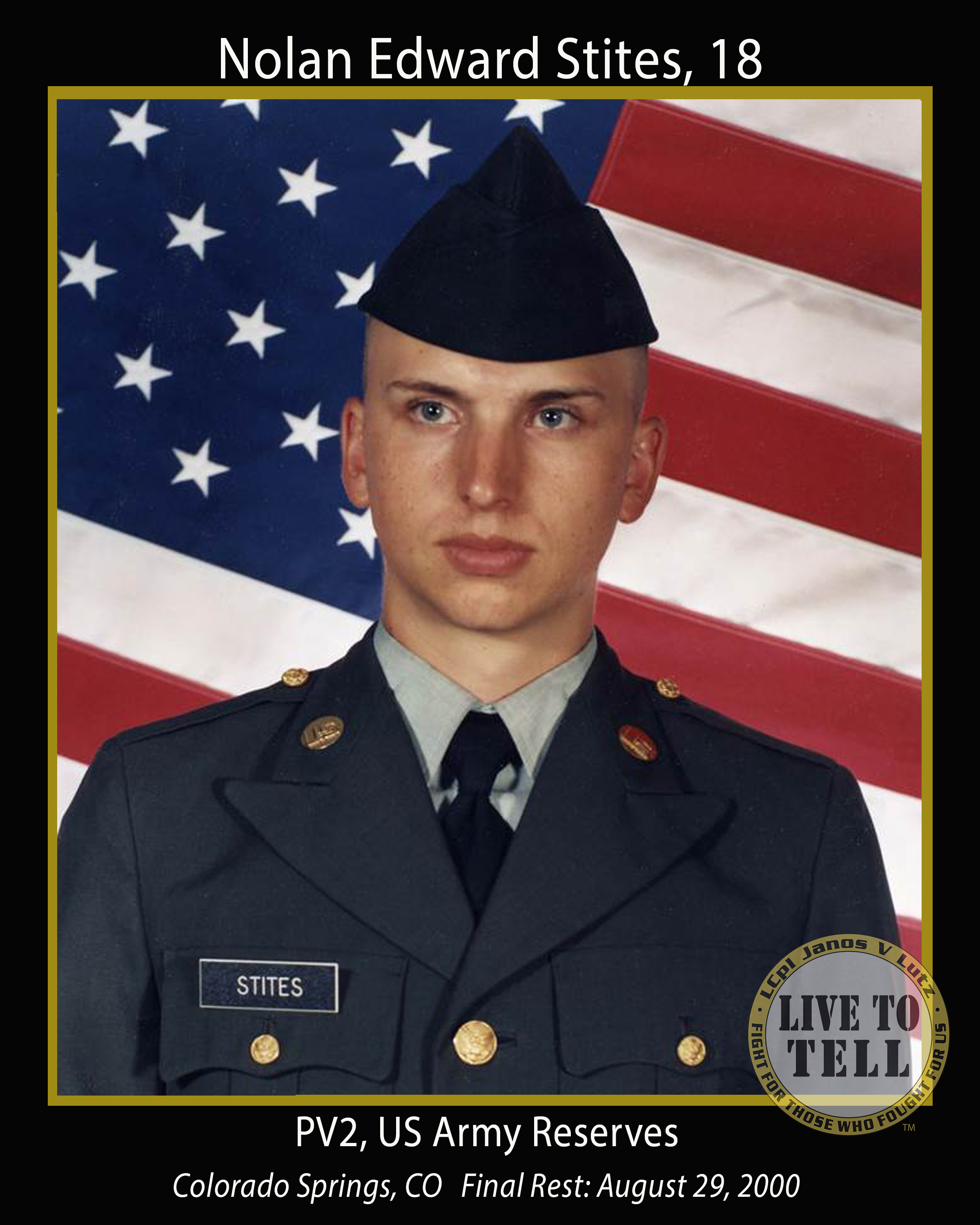

My son, Nolan Edward Stites, was an Army Reservist assigned to the 52nd Combat Engineer Battalion on Fort Carson, Colorado. He successfully completed nine months in the Army Reserve “delayed entry” program with the 52nd Engineers and received a promotion due to his excellent performance. In the summer of 2000 he reported to Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri for Basic Combat Training where he became ill with clinical depression shortly thereafter. Nolan sought help for his illness and was a patient under care of the U.S. Army when he died during his seventh week on the Missouri army post.

Nolan graduated from high school with honors, never got into trouble and was respected as mature by all adults that knew him. He was an active church member, did not smoke, drink, use drugs or have any history of mental or family problems. Nolan was a rugged and physically fit outdoorsman, expert marksman with all types of firearms and loved the military. He held high ideals and was very patriotic. Nolan’s many NCO and Officer Friends familiar with his out-door skills and endurance considered Nolan potentially a model soldier.

During his second week at Fort Leonard Wood, Nolan complained of the heat and humidity and said his forehead was severely sunburned and swollen. Nolan, a native of Colorado, was not acclimated to Missouri’s climate in July. Two weeks later he called home and reported leg cramps, insomnia, loss of appetite and cognitive problems with reading, writing and understanding what was being said to him. I, as his father, advised him to seek medical care on post, a recruit’s only source of help. Nolan, being one not to complain, tried to tough it out and continued training until his ailments progressed to bladder control problems, making it impossible to go on. He went to his roommates, drill sergeants and finally the Brigade Chaplain for assistance.

Nolan told the Chaplain he was depressed and had suicidal thoughts, a common symptom of depression. The Chaplain recognized Nolan needed to be seen by a mental health professional and, as required in this type of case, reported his findings to the Company Commander. The Company Commander immediately removed Nolan from training and put him on “Suicide Unit Watch,” the Standard Operational Procedure in use at that time. According to the Captain, Nolan ranked in the top 10% of the company when he placed my son on unit watch.

As viewed by many enlisted personnel, unit suicide watch is a disciplinary program of humiliation and ostracism used by the military to deter manipulative recruits from claiming mental problems to get out of the service. They removed Nolan from all training but not the unit; made him sleep in the War Room, using tired, resentful, and untrained teenagers to guard him at night. Without any medical treatment, Nolan was forced to parade around in front of his peers for fifteen days, minus belt and bootlaces. Ostracized from training and humiliated as a marked man, Nolan was so distraught over his situation he told a roommate he was considering ending his life by jumping from the third story window. The worried roommates got together and one wrote their platoon sergeant a note expressing their concerns but to no avail; their note went ignored!

On the fifth day of his unit watch ordeal, Nolan saw an Army social worker that misdiagnosed him as “a Special Ed. student that never got help” and “unfit for service.” (Nolan had just graduated from high school with a grade point average above 3.5.) The social worker returned Nolan to the barracks on full “Unit Watch” without further follow-up for the last ten days of his life. On unit watch, Nolan was subjected to sleep deprivation, humiliation, and embarrassment. I have several reports of Nolan being made fun of and in one case, in front of the entire platoon, a drill sergeant told Nolan he was holding the whole platoon back, that they would be better off without him, that he should kill himself, challenged Nolan to jump from the third floor and even offered to open the window. (This kind of mental abuse is devastating to a patient suffering and struggling to overcome clinical depression.) Fighting for his life Nolan wrote his platoon sergeant a note pleading for help, “nobody will help now but I need emergency help to live, my parents want me to live and so do I.” He then apologized for causing the platoon trouble. The platoon sergeant failed to take appropriate action, no doctor saw the note until after Nolan’s death.

After two weeks of unit watch my son called home about his desperate situation. I then called the Red Cross for help but they misspelled Nolan’s last name so bad they had difficulty in locating him on Fort Leonard Wood. Over the telephone, eight hundred miles away, I told the platoon sergeant to take Nolan to the hospital. After examining Nolan, the ER doctor gave him an I.V. for dehydration, set up an appointment with the mental health service for the next day and returned Nolan back to the barracks for more “unit watch.” The platoon sergeant placed Nolan next to a window on the third floor. Nolan saw no hope for help and wrote a farewell letter to his family stating, he didn’t know how to get help, there was only one place left for him to go, and “God could never forgive me for disgracing my country and my family.” Stripped of his self-esteem with “no light at the end of the tunnel,” my son, PV2 Stites, did as his sergeant told him to do, jump to his death!

A year later I received a pathetically flawed CID investigation report through FOIA. It did not explain the pencil point size puncture wound to my son’s abdomen, inconsistent with injuries sustained from landing on his back. The CID agent in charge of the investigation photographed another recruit’s ID tag at the death scene and identified it as Nolan’s without reading it. The broken chain from the tag was in blood, two inches from my son’s right ear. Nolan was right handed and his body position was face up. The other boy’s ID tag was sent to us in my son’s personal possessions. Based on my research about unit watch, I was certain my son had been abused but because of the Feres Doctrine I was not allowed to sue and subpoena witnesses to discover the truth.

If a soldier is suicidal he doesn’t belong in the unit, if he is not suicidal, why take away his belt and bootlaces to mark and humiliate him in front of his peers? Intentional or not that defines what unit watch is all about, punishment for saying you are ill. Nolan’s death did not result from an accidental slip of a surgeon’s knife but 15 days of mental abuse. No one intended Nolan bodily harm but out of ignorance their actions precipitated his death. The culprit in this case was not any one individual but the government of the United States for allowing this sadistic and abusive program to exist! Without accountability nothing changes.

The military has experienced a high suicide rate in recent years. How disingenuous it is for the military to complain about the “stigma” that prevents soldiers from seeking help when for many years “stigma” was taught in basic training. Recruits learn very quickly to expect abuse if you seek help for mental or emotional problems.

Five weeks earlier, another recruit, PVT Gary Moore from our state of Colorado, also killed himself on Fort Leonard Wood after suffering three weeks of abuse and being made fun of on “Unit Watch.” Both of our families were denied redress when we filed Tort claims for gross negligence and medical malpractice, resulting in death. The government using the Feres Doctrine responded with a letter denying our claims stating, “The United States is not liable to service members under the FTCA for injuries that arise out of or are in the course of activity incident to service.”

In Nolan’s case no one was held accountable or punished; the sergeant that told Nolan to kill himself was horrified by what he did and admitted it to the CID. He offered to surrender his rank and resign from the army but instead was sent to the drill sergeant school as an instructor where he received awards for excellence and promoted. He told his trainees, “Words have meaning; you have to be careful what you say to people.”

None of this is in the CID report I received from the government, it was sanitized for our family’s consumption. I learned about what happened to my son from over a dozen eyewitnesses, people I managed to contact and strangers who contacted me a decade later to get what they witnessed off their chest.

Our and Gary Moore’s family discovered, like many other families of deceased active duty soldiers who died wrongful deaths, the Federal government puts itself above the law and there is little you can do about it.

Richard R. Stites, AKA, “Singe”

Father of the late PV2 Nolan Edward Stites.

These words from a father very much say what i said when i tried to find out information into my brothers death on december 15th 1977 he hung himself in a hospital closet my brother was a military policeman a sergeant who had marital problems over custody of his 3year old son. I tried desperately to try and find out more information on his death but was told i wasnt next of kin and any information i could request from his wife to this day i grieve for loss of my brother moreso because i could never get any information from the US Army or the Us Embassy i am English and my brother became an American citizen to join the service i will never give up on him until I die because i haver had a satisfactory answer about his death and every time i see the loss of yet another young man i cant help but wonder what goes on to make these brave and courageous guys take their lives all young men who were prepared to give their lives for country yet are so desperate they take their own lives to the grief of each and everyone of their families condolences to every family going through this grief God Bless them all may they rest in peace

I was in C-148 with your son I everything you wrote is 100 percent accurate.in the 19 years since that horrible day his face and name has crossed my mind over a million times I’ve never recovered from what my 18 year old eyes witnessed leading up to and the aftermath RIP to your son God bless