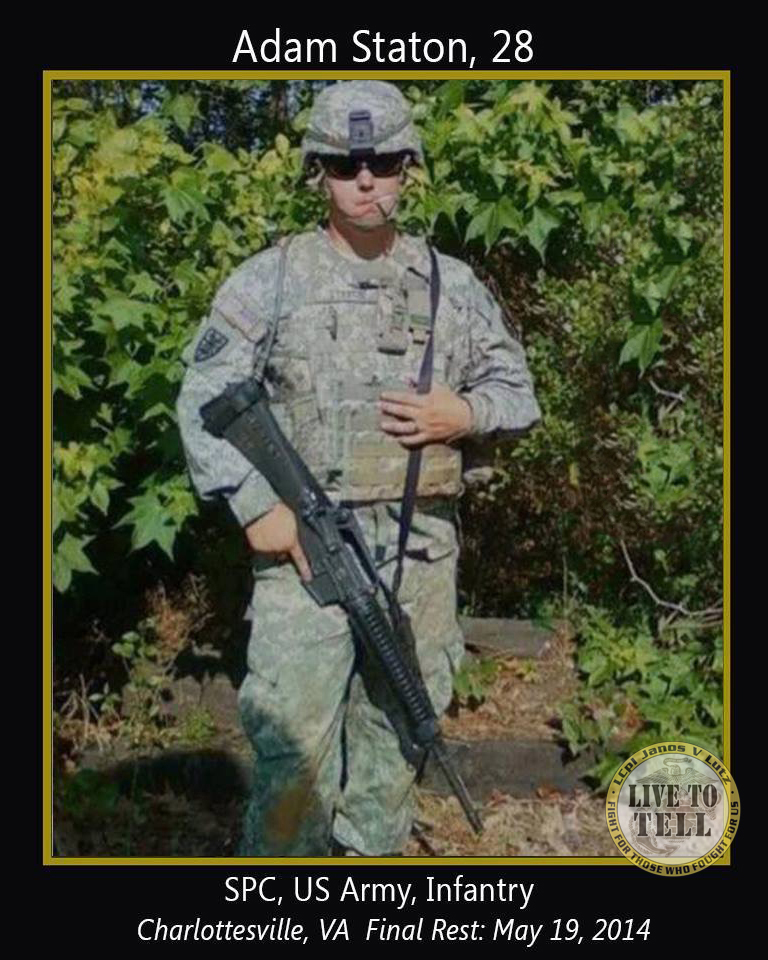

Army Specialist Adam Ross Staton, born May of 1986, in Charlottesville, Virginia.

Adam served his country proudly and spent time in the combat zone as an Infantryman.

He was an amazing father and touched many lives.

SPC Adam Staton lost his battle on May 19, 2014. He was 28 years old.

Shared from Carry the Wounded:

‘He never left my side:’ Spouse torn between saving her family, her husband and his career

“Mere moments into her first conversation with him, she was overcome with a peaceful bliss.

“I knew the day I met him,” said Amber Staton, reminiscing about her introduction to 18-year-old Adam Ross Staton, whom she eventually fell in love with and married. “He never left my side from that minute.”

Even more convincing, Adam also had won over Amber’s son, who had shown himself to be comfortable with only one other man – his grandfather, said Amber.

Adam was the “most easygoing person I ever met,” said Amber, “a person everyone liked.”

That endearing personality, however, was not present when Adam returned from a year-long deployment to Kuwait in 2009. He was distant, preoccupied and lacked the persona that endeared him to so many, said Amber. Adam’s troubled mental state eventually forced him out of the Army and precipitated a separation from his wife and two kids.

Although they lived apart, the two Fredericksburg natives talked on a regular basis. One morning after working the overnight shift at a hotel in 2014, Amber went home and retired with a sense of uneasiness after not receiving a call from her husband; the feeling one gets when something has happened to a loved one.

What she felt was grounded in truth.

Amber was awakened to the sound of a buzzing cellphone, and the subsequent gloomy message delivered by her brother-in-law.

Adam had ended his life. He left a voice message recorded during the throes of his decisive action, expressing love for family members while dealing them the most crushing blow.

“My whole world just went numb,” recalled a sniffling Amber. “I didn’t know what to think or do, or who to call or how to tell the kids.”

Adam’s decision brought to a close a tumultuous five-year period marked by family strife and instability.

It also birthed in Amber feelings of guilt and thoughts of reflective contemplation. Perhaps, most surprisingly, Adam’s death became the impetus to spare others the paralyzing devastation of losing a loved one.

“I want to help other people,” said Amber, who recently earned a two-year degree in social work. “Eventually, I want to become a licensed clinical social worker and help people through crises.”

Amber’s crisis began with her husband’s 2008 deployment to Kuwait. He was assigned to the 7th Sustainment Brigade at Joint Base Langley-Eustis. Its mission was to provide logistics support in a country that acted as a staging base for coalition combat activities in Iraq and Afghanistan.

“He seemed great,” Amber said, recalling the mood of her husband prior to his first deployment. “He was sad to go but excited to serve his country.”

While her husband was away, Amber said she kept in touch with him via Skype. He didn’t talk much about his particular job – only that it involved “security things,” she recalled.

Amber eventually noted some stress in her husband, and the fact he began to argue about things they never bickered about. Questions such as “Whom were you with?” and “Where were you when I called?” would launch him into intense diatribes.

“I played it off as being far apart from each other,” said Amber.

As if her husband’s issues were not enough, Amber essentially had her own as a single mom. She began to cultivate her role as a superwoman, someone who could cook, clean and tend to the kids – all in a single bound. And she full-well required a cape. Her 6-year-old was quite active and her special needs toddler eventually became wheelchair-bound and required a load of support services. For her, it was important to maintain the image of control, strength and authority.

“I had to show them I was strong enough to conquer this,” she said, noting she shed tears on many nights from the weight of her responsibilities and leaned heavily on family and friends for support. “This was just one year; we can get through it, and we’ll be fine.”

Amber said she also put on a positive face with Adam. “He had enough going on, and I didn’t want him to worry,” she said.

Adam redeployed in August of 2009. The family went on a Disney cruise to celebrate. That’s when something jumped out at Amber.

“He was drinking more and drinking in front of our kids,” she said, noting they had both vowed they would abstain from such behavior. She later dismissed his actions as transitional.

When the vacation ended and the family returned home, things were different. The Staton household was Amber’s domain. She had become quite independent in running the home, mastering schedules and routines with a high degree of precision. Adam struggled to integrate himself into the flow of things.

“He started spending less time with us,” said Amber. “He just wanted to be alone and play his PlayStation.”

She gave him his space.

Adam’s relationship with his family wasn’t improving, however, and the bickering evolved into something greater. “I think I knew something was off at that point,” recalled Amber.

An acknowledgement of their troubles moved Amber to sign up for a chaplain-sponsored marriage retreat in late 2009. “He thought it was a great idea,” she said of her husband, but it went horribly wrong. They argued during the occasion and then returned home where it got worse, causing one of the neighbors to notify police.

“They called me in, and I played it off,” she said. “I didn’t want him to get into trouble.”

Aside from Amber’s reluctance to alert authorities, She said Adam was in a place in which he could not accept responsibility for his actions. “He wouldn’t admit anything,” she said, noting “everything was my fault.”

Still thinking like someone who wanted to save her family while simultaneously working to preserve her husband’s career, Amber decided to contact Military OneSource, a Department of Defense program that offers a plethora of services for military members and families. It led to free counseling sessions at a private practice.

“He went twice and didn’t want to do it anymore,” she said, noting Adam did it to appease her “because he knew I wouldn’t let up” in light of the recent events.

Adam’s estranged behavior continued even through the death of Amber’s mom in early 2010. The couple was separated on several occasions due to the constant turmoil and the emotional blows it inflicted upon the children, especially the oldest, who played out much of what he saw between his parents.

“He became aggressive and (eventually) got kicked out of school,” said Amber of her son who was 8 at the time.

Still, Adam became worse. He threatened to commit suicide later in 2010 and was admitted to a hospital but released a short time later. His command directed all the firearms be removed from the couples’ on-post residence.

“It scared me because I knew then he was not in his right state of mind,” said Amber, now the caretaker for her heavily medicated husband who was still a threat to himself. “He was never the same again,” she remembered.

Amber was at a crossroads. She was exhausted from the strains of her relationship and the demands of running a household. She also was dealing with medical issues of her own, nonetheless, she didn’t feel right abandoning her husband.

“Honestly, I did love him and I didn’t want the kids to not have their daddy,” she said.

She stayed.

In late 2012, Amber said the situation became unbearable. She ‘snuck off’ while Adam was at work and moved to Northern Virginia to live with her father. During phone conversations, he would often ask her when they could live together again. She was tired of making sacrifices.

“You have to be willing to get help,” Amber said she told him. “He would say, ‘Oh, I’ll get it,’ but he never did.”

In May of 2013, Adam was discharged from the Army. He moved in with a relative in Northern Virginia and saw his kids as much as he could. After her father passed away, Amber moved to Petersburg to cut costs. They continued to talk regularly.

Adam moved to South Carolina roughly a year later to live with another relative, said Amber. Having held and lost several jobs, it was apparent he was still having problems.

“I could tell he was still depressed,” she said. “We would talk on the phone for hours because I was working the night shift at a hotel.”

During a visit to Petersburg in May of 2014, Adam took his family out for dinner. Amber held out hope her husband would be better but in actuality his decline was further along than she imagined.

“He had no emotion,” she recalled. “He was just numb.” Amber looked to her husband for reassurance. “Everything’s all right,” Adam said, a sure sign he lacked the power to gauge his own condition much less accept it.

The 28-year-old’s visit to Petersburg was the last he would see of his wife and sons. He died May 19, 2014. Adam was one of nearly 1,900 veterans who took their lives that year, according to the Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America.

In the aftermath, Amber and other family members were consumed with guilt and suppositions.

“There were so many ‘what ifs’ and ‘whys’ of what happened,” she said. “The truth is, before this happened, he was the person I never suspected would kill himself because he thought suicide was the most selfish thing in the whole world.”

Today, Amber said she still feels some guilt and wishes she had paid more attention to the warning signs.

“My biggest downfall was letting this go as long as I did without ever doing something major,” she said.

“Yes, it could have affected his career, but I shouldn’t have held what I was going through secretly. Had I pushed it out to the light, he would have had access to more services. Maybe that wouldn’t have helped him when he got out, but at least for the time, he could have gotten the help he needed.”

Additionally, Amber said it is imperative to champion the well-being of loved ones no matter the circumstances.

“What I realize most of all is they’re not capable of saying whether they need help and so we almost have to be like parents and be their advocate even though they don’t want us to be,” she said.

Finally, more resources should be made available to bolster the services of the Department of Veterans Affairs, in her opinion. “The VA is not bad because they do help many people,” she said, “but they’re understaffed and there’s just not enough of their services to help all the veterans out there.”

The VA has hired thousands of medical and mental health professionals over the past few years and has dramatically reduced its backlog. It continues to make improvements, according to its website.”

Specialist Adam Ross Staton, US Army

Specialist Adam Ross Staton, US Army

Quantico National Cemetery, Section 25 Site 265

Quantico, Virginia, USA